Long Range Attacks, and a new Fork Choice Rule

In this blog post we briefly discuss the concept of long range attacks, which is considered to be one of the biggest unsolved problems in Proof-of-Stake protocols. We then cover two solutions presently used in live or proposed protocols, namely weak subjectivity and forward-secure keys. Finally, we present a new fork choice rule that makes long range attacks significantly more expensive. The fork choice rule presented can be combined with either or both existing solutions, and can serve as an extra measure against the long range attacks.

This write-up is part of an ongoing effort to create high quality technical content about blockchain protocols and related topics. See our blog posts on Layer 2 approaches, Randomness, and our sharding paper that includes a great overview of the current state of the art.

Follow us on Twitter or join our discord channel to make sure you don’t miss the updates.

Long Range Attacks

Proof-of-Work with the heaviest chain fork choice rule has a very desirable property that no matter what malicious actors do, unless they control more than 50% of the hash power, they cannot revert a block that was finalized sufficiently long ago.

Proof-of-Stake systems do not have the same property. In particular, after the block producers that created blocks at some point in the past get their staked tokens back, the keys that they used to create blocks no longer have value for them. Thus, an adversary can attempt to buy such keys for a price significantly lower than the amount of tokens that was staked when the key was used to produce blocks. Since, unlike in Proof-of-Work, Proof-of-Stake has no mechanism to force a delay between produced blocks, the adversary can then in minutes create a chain that is longer than the canonical chain, and have such chain chosen by the fork choice rule.

There are two primary ways to get around this problem:

Weak subjectivity. Require that all the nodes in the network periodically check what is the latest produced block, and disallow reorgs that go too far into the past. If the nodes check the chain more frequently than the time it takes to unstake tokens, they will never choose a longer chain produced by an adversary who acquired keys for which the tokens were unstaked.

The weak side of the weak subjectivity approach is that while the existing nodes won’t be fooled by the attacker, all the new nodes that spin up for the first time will have no information to tell which chain was created first, and will choose the longer chain produced by the attacker. To avoid it, they need to somehow learn off-chain about the canonical chain, effectively forcing them to identify someone whom they trust in the network.

Forward-secure keys. Another approach is to make the block producers destroy the keys that they used to produce blocks immediately or shortly after the blocks were produced. This can be done by either creating a new key pair every time the participant creates blocks, or by using a construction called Forward-secure keys, which allows a secret key to change while the corresponding public key remains constant.

This approach relies on nodes being honest and following protocol strictly. There’s no incentive for them to destroy their keys, since they know in the future someone might attempt to buy them, thus the key has some non-zero value. While it is unlikely that a large percentage of block producers at a certain moment all decide to alter their binaries and remove the logic that wipes the keys, a protocol that relies on the majority of participants being honest has different security guarantees than a protocol that relies on the majority of participants being reasonable. Proof-of-work works for as long as more than half of the participants are reasonable and do not cooperate, and it is desirable to have the fork choice rule and a Sybil resistance mechanism that have the same property.

Proposed Fork-Choice Rule

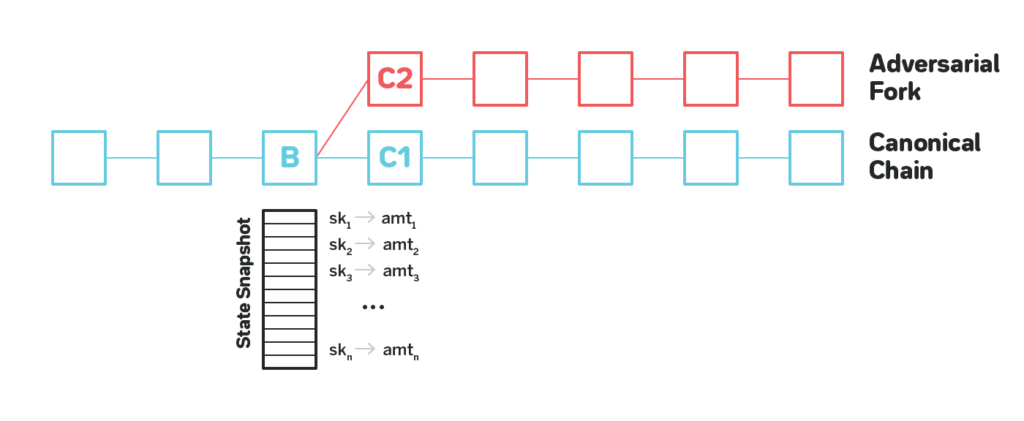

Consider the figure below. There’s a block B sufficiently far in the past on the canonical chain such that the majority (or all) the block producers who were building the chain back when B was produced have their stake unstaked.

The adversary reaches out to all those block producers and acquires the private keys of ~⅔ of them. At that point the keys have no value to the block producers, so the adversary can purchase them for a price significantly lower than the actual amount that was staked.

The adversary then uses the keys to build a longer chain. Since no scarce resource is used in a Proof-of-Stake system, the adversary can do it very quickly.

We want a fork choice rule such that no matter how long the chain the adversary has built is, and how many of the corrupted validators signed on it, no client, including the clients that start for the first time, will see the chain built by the adversary as the canonical.

The proposed fork choice rule is the following: start from the genesis, and at each block greedily choose one of its children as the next block by doing the following:

- Snapshot the state as of after the current block is applied.

- Enumerate all the accounts that have tokens at that moment, as a list of pairs (public key, amount).

- For each child block, identify all the public keys from the set that signed at least one transaction in the subtree of that child block.

- Choose the child block for which the score, computed as the sum of the amounts on the accounts that signed at least one transaction in its subtree, is the largest.

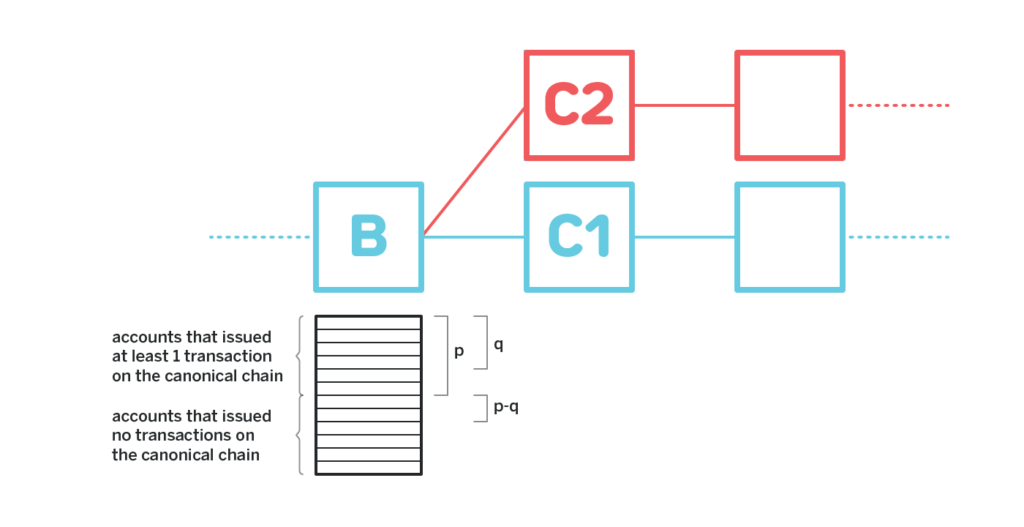

In the example above if the current block we consider is B, its child blocks are C1 and C2. The subtree of C1 is all the blocks ever built on the canonical chain, while the subtree of C2 is all the blocks built by the adversary.

The score of the canonical chain will be the sum of all the amounts on the accounts in the snapshot that issued at least one transaction throughout the history of the canonical chain starting from B, including all the money transfers and staking transactions.

The score of the adversarial chain will be the sum of all the amounts on the accounts that made a transaction on the adversarial chain. With a proper replay protection it means that all such transactions will have to be issued by the adversary.

Say the total amount on all the accounts that exist in the snapshot that made at least one transaction on the canonical chain since B is p. Say the adversary managed to purchase the keys for a subset of such accounts such that the total amount on them adds up to q, q < p. Since for the adversary to have a heavier chain they need the total amount of accounts that issued transactions to be more than p, they need to also get a hold of some keys that correspond to accounts with more than p – q tokens for which no transaction was issued on the canonical chain. But since for those accounts no transaction was issued on the canonical chain, the keys for those accounts cannot be acquired for less than the value that was on such accounts in the snapshot, since those accounts still have all the funds that were in the snapshot as of the latest block on the canonical chain.

Thus, if the adversary can realistically acquire the keys as of block B that correspond to 80% of all the accounts that issued at least one transaction on the canonical chain at a discount, they still need to pay the amount of money that is at least 0.2p.

Note that this fork choice rule only works for long range fork decisions, since for the canonical chain to be resilient to forks, it needs to accumulate a large number of accounts issuing transactions. One way to combine it with more classic fork choice rules would be to first build a subset of the blockchain that only consists of blocks finalized by a BFT finality gadget, run the fork choice rule described above on such a sub-blockchain, and then starting from the last finalized block on the chain chosen by the fork choice rule use a more appropriate fork choice rule, such as LMD GHOST.

Outro

The fork choice rule described above provides an extra level of protection against long range attacks.

This particular fork choice rule, while has interesting properties, needs to be researched further before becoming usable in practice. For instance, it is unclear without further analysis if it provides economic finality.

We are actively researching the approaches to defend against long range attacks presently, and will likely be publishing more materials soon, so stay tuned.

In our continuous effort to create high quality technical content, we run a video series in which we talk to the founders and core developers of other protocols, we have episodes with Ethereum Serenity, Cosmos, Polkadot, Ontology, QuarkChain and many others. All the episodes are conveniently assembled into a playlist here.

If you are interested to learn more about technology behind NEAR Protocol, make sure to check out our sharding paper and our randomness beacon. NEAR is one of the very few protocols that addresses the state validity and data availability problems in sharding, and the sharding paper contains great overview of sharding in general and its challenges besides presenting our approach.

While scalability is a big concern for blockchains today, a bigger concern is usability. We invest a lot of effort into building the most usable blockchain. We published an overview of the challenges that the blockchain protocols face today with usability, and how they can be addressed here.

Follow us on Twitter and join our Discord chat where we discuss all the topics related to tech, economics, governance and other aspects of building a protocol.

Share this:

Join the community:

Follow NEAR:

More posts from our blog